WASHINGTON, (Soldiers Magazine, Jan. 26, 2011) -- In the glitz and glamour of Hollywood, appearance is almost everything and plastic surgery - to achieve the perfect body, the perfect face, and perfect skin - is commonplace if tabloids and TV shows can be believed.

So, as soap opera star J.R. Martinez of "All My Children" sees it, he fits right in. After all, he's had more than 30 surgeries. The only difference between Martinez and other young actors: Instead of getting a nose job or Botox shots from high-priced Beverly Hills surgeons, Martinez spent more than two years at Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio, undergoing skin grafts and treatments for burns that covered 40 percent of his body.

That's because Martinez - who plays Brot Monroe, an Army veteran burned in combat - used to be Cpl. J.R. Martinez of the 101st Airborne Division. He deployed to Iraq during the initial invasion in March 2003 at the age of 19, only six months after enlisting, still so green he wasn't sure he could find Iraq on a map. Less than a month later, April 5, the front left tire of the Humvee he was driving hit a landmine. Three other Soldiers were thrown from the vehicle and sustained mostly minor injuries, but he was trapped inside.

Minutes before, he and the Soldier riding shotgun had been joking about how cool it would be to get a Purple Heart and not have to wait in line at restaurants back in the States.

"The things you say and never think it's going to lead to anything," he remembered, "because humor is the biggest thing you've got to maintain while you're over there. That's what keeps you going."

But it wasn't cool, and instead of laughing, he was soon screaming for help as smoke filled the Humvee and flames consumed him.

"It's going to end for me. This is it," he thought.

Raised by a single mother, Maria Zavala, who had emigrated from El Salvador and had already lost one child, he realized that there was no way he could put her through that again. He had to hang on. By the time his buddies were able to get him out (Martinez later learned insurgents had attacked their convoy as soon as the landmine went off), 10 or 15 minutes had gone by and, conscious the entire time, he was in unspeakable pain.

"It's really hard to explain," Martinez said. "You know how you burn yourself on an iron or stove and how painful that is, or maybe a sunburn, and the pain is just excruciating' This was just on-another-world-, on-another-universe-painful. It was just so far beyond what I had ever known and what I've ever experienced that there's no way to explain it. It's an unbearable pain. Burns are something I would never wish upon my worst enemy."

The third-degree burns were so deep, and he lost so much fluid and tissue, that after a while, they destroyed the nerves. The smoke damage was so severe that his lungs and other organs began to shut down. Martinez was put in a medically induced coma for the pain-that and because he kept trying to touch his face, thinking he could make it feel cooler.

One of the medics later told him that he had to be strapped to his bed at the evacuation hospital after he bounced up and told everyone to leave him alone because he was "fine." In reality, when he arrived at BAMC four days later, doctors still weren't sure if he would make it, and kept him in the coma for almost three weeks.

After he came out of it, he remained completely dependant on others for weeks, and nurses escorted him to the showers every morning for debridement (removing the dead, scarred skin), which Martinez said was even more painful than the initial burns. But after several days of the torture, he became suspicious: "What the hell is going on' Why is this so painful' What does it hurt so much'" he thought, and demanded to see a mirror, although his doctors and nurses were vehemently opposed. They thought it was too soon and would be traumatic, but Martinez insisted.

"'I want to see my face. I want to see my body, now,'" he told them, explaining that he was the one who would have to live with it for the rest of his life. Why bother putting it off? It would be just as devastating later, so surely it was better to get it over with. When they finally agreed and sat him in front of a mirror, the sight of his face, neck and hands was a shock that sent him into a depression so deep, he began to wonder if he would have been better off dying in that Humvee.

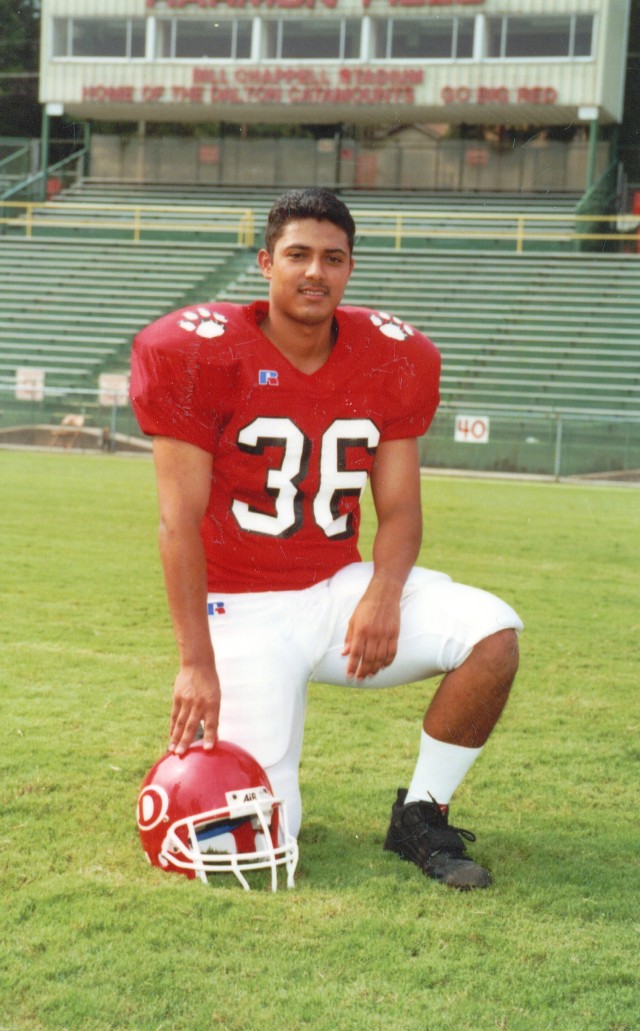

The life he had dreamed of was certainly back in its burned out shell. At the age of 19, he was no longer the handsome young athlete everyone had talked about, and he no longer knew how he would ever find a girlfriend, let alone get married or have children.

"I just felt, looking at my body, there's no way I'm ever going to be able to experience that," he said. "My life was spared, but for what?"

Martinez grieved for the man he had been, only going through the motions of his recovery, wondering what he had done to deserve such a punishment, until about five weeks after he had arrived at the hospital when his mother -- who had gone through her own ordeal watching her only son face death and disfigurement -- snapped him out of it. She explained that he had a lot to learn about life. Looks weren't everything. In fact, she joked, she was proof.

"'People are going to be in your life for who you are as a person and not what you look like,'" she told him. "'I remember when I was younger, everyone told me I was pretty and gave me compliments. No one tells me that now.'"

Something clicked and Martinez immediately answered, "'You know what, Mom? You're right. And now, I'm actually glad this happened to me.'"

"'Wait a minute, what do you mean you're happy?"

"'Now I get to see who liked me as a person, versus who liked me for being the popular guy in school, being the athlete, being the handsome young man. Now I get to see who really loves me or likes me for who I am as a person,'" he said. In that instant he understood, and he suddenly had a new mission.

Between his 32 (eventually 33) surgeries, and therapies to stretch his tender, growing skin (he even had to wear a mask to compress the scarring on his face), Martinez began to visit other, newly wounded servicemembers on the wards at BAMC. They too were often badly burned, some with faces that had been nearly charred off. They too were devastated and sometimes didn't want to go on living, but Martinez noticed that after he talked to them, they seemed to cope a little better.

"I said to myself, 'I think this is my gift. I'm going to share my gift with other wounded troops because a lot of these guys are arriving here without a clue of what to expect. I've been through it. Maybe I can just kind of help them and prepare them on what to expect.' So I started visiting patients on the wards every day," he explained.

The local and then national media began to pick up his story, and before he knew it, he was in the Washington Post and on "60 Minutes" and "Oprah," talking about hope and renewal, explaining that if wounded warriors could just find the strength they had in battle, or even when they enlisted, they could make it through this war too.

Due to his heavy scarring, Martinez is used to getting some strange looks when he hits the streets, and he wants injured servicemembers, burn victims and other people with disfigurements to know that that's OK. In fact, he embraces the strange looks, and if someone wants to ask about his scars, that's fine too, because Martinez views the looks and questions as opportunities to educate people about true beauty.

"We have the power," he explained. "The more we sit there, the more we accept the unfortunate things that have happened, the more we embrace those things and own them, we have the power to actually change the mindset and allow these people to be completely comfortable with scarring, with disfigurement. But what we have to do is go out to the public. We can't be afraid. We have to step up and say we're going to go out there, because the more they see, the more they start to say, 'OK, you know what' There's nothing wrong with it. It's unfortunate, but it's kind of common.'"

In 2006, when one of his noncommissioned officers urged him to stay in the Army and continue motivating other Soldiers after he was finally discharged from BAMC, Martinez explained that his new uniform was his scarred skin, and his new weapons were his words. He spent two years doing motivational speaking and nonprofit work for wounded troops, and then one day in 2008 he got an e-mail: "All My Children" had decided to launch a short-term storyline about the difficulties returning veterans faced, and thought it might be interesting to cast the role with a real veteran. Martinez had no acting experience, but he had done hundreds of speaking events at that point, and figured he had nothing to lose by auditioning.

Getting the role of Brot Monroe, who had let his fiancee and family believe he was dead rather than let them see his scars, was surreal to Martinez, especially because during his recovery at BAMC, while forced to watch his mother's telenovelas every night from his hospital bed, he had joked with her that he would be on a soap one day. He already knew the plot and everything: Man gets beautiful girl. Man is in car accident or fire. Girl visits man in hospital. Man turns out to be Martinez. Martinez gets beautiful girl.

Things have been far from that straightforward for Brot as he struggles to come to terms with his scars and civilian life in fictional Pine Valley, Pa., but he has connected with audiences. Martinez's three-month stint became a long-term contract, with Brot joining the local police force, and even finding possible romance with a beautiful lady detective. The show's writers and producers, Martinez said, try to be as accurate as possible, and give him a lot of input. They even incorporated his 33rd surgery last summer to fix one of his eyelids into "All My Children's" storyline.

While his character carries a lot of anger and grief, and occasionally lashes out at friends and coworkers, Martinez hasn't found those scenes to be especially painful, explaining that because he has already worked through his own pain, he can go to that place for the scene and then turn his emotions off. Many viewers are actually surprised that he's a real veteran and not a regular actor wearing heavy makeup, waiting for a "miracle" plastic surgery cure.

"I remember one day sitting in Grand Central Station (in New York), waiting for a friend, and all of a sudden a guy's walking by and he said, 'Are you guys filming a scene here'' At first it's understandable that people think it's makeup because TV does crazy things. However, it's nice for people to understand and learn over time that it's real and become educated about it," Martinez explained, adding that "All My Children" is a great way for him to educate people about wounded Soldiers and motivate people going through their own battles.

Martinez is writing a book about his experiences, and hopes to have his own talk show some day. In the mean time, he still does a host of motivational speaking and charity work on behalf of wounded troops, who he'll often invite to the show's new Los Angeles set (the show, and Martinez, just moved to LA from New York). In time-honored military tradition, once they've finished making fun of him for acting on a soap opera, and bonding over shared experiences, Martinez explains that it might be his name and face out there, but that's it. He's out there for them. They inspire him. He's been home from war for seven years, so recently returning vets are fighting for his freedom as much as anyone else's, and he has a debt to repay.

"Although a lot of these guys say that I inspire them, a lot of them inspire me," Martinez said. "When I'm having a bad day, I just think about a lot of them, and I just think, 'What am I sitting here complaining about' These guys have gone through so much more.'"

Comments

Post a Comment